Legacy

This article was published in Goldenseal magazine (Summer 2006, pp. 46-51). The article is not on line, but the magazine website is: http://www.wvculture.org/goldenseal/index.html

OVER THE HILL IS OUT

by Karl Priest

The largest public housing project ever built in West Virginia opened in the summer of 1955 in a pocket between Charleston’s West Side and North Charleston. Trees hid the neighborhood along Route 21 and a mountain curved around most of the rest of the area where the project was built. The best view of the conglomeration of dozens of red brick buildings containing 360 apartments was a narrow opening at the project’s entrance on West Washington Street. Most vehicles took a more convenient route to North Charleston. After the initial publicity, most people would have forgotten the complex existed had it not been for continuing newspaper notoriety.

Taking its name from the apple orchard it replaced, Orchard Manor was home to about 1500 of Charleston’s poorest residents. Many of the families were fatherless, and many of the fathers, who were present, abused alcohol. Life in “The Manor”, as it became known, was a mixture of typical neighborhood interaction and inter-city ghetto realities. Contrary to the utopian hopes of the politicians who facilitated construction of the housing project it was mostly the latter. Those stories can be found in old newspaper headlines and police blotters. Within the culture of crime and violence that engulfed The Manor, behind one of the brick apartment buildings that lined the dangerous streets, there was another world lived out by a group of baseball playing boys.

I arrived, as an eight year old, in the Manor in the spring of 1956 with my parents who were raised on self sufficient farms. My father (Howard Priest) was from Braxton County, West Virginia. My mother (Ruby Justice) arrived in Charleston from Martin County, Kentucky. I was an only child, but hardly noticed it because I was surrounded by so many other kids and quickly welcomed to the mini-society of serious baseball players.

There were no video games or color television to occupy a boy’s time. Almost every summer day, a couple of boys would start passing a baseball behind my row house building which sat diagonally across the street from our ball field. The other boys, who all lived in apartments without air-conditioning, were drawn outside by the sound of rawhide slapping leather. They arrived wearing shorts or tattered jeans; with T-shirts or bare chests; their heads usually covered by a beloved baseball cap with precisely bent bill and a carefully formed tuck behind the team letter. Some were bare footed, but all wore spikes and major league uniforms in their imaginations. A few came on bicycles with their baseball glove dangling from the handle bars, but most walked with their gloves on their hands as they spat into and banged the pocket with the opposite fist. We would play pepper or ball-strike pitching games, using a garbage pit as a backstop, until enough boys gathered around. Then we would cross the street to begin the baseball game that would go on for hours—starting with the afternoon sweat bees and ending with the evening mosquitoes.

We played baseball behind a four-story apartment building. There was playground equipment scattered in three open areas among the project, but the area behind the building was large enough to be used as a baseball field. In reality there was only enough outfield space for center field so we had to agree on rules to accommodate the unique “design” of our playing field. Home plate (as were all of the other bases) was actually a piece of card-board. The “plate” was located about 250 feet from straight-away center field. Center field ended on a small hill bordering a street that curved away from left field making right-center a distance of about 325 feet

Most of right field dropped down over a hill onto a narrow level area and then on down a steep hill to Kanawha Two-Mile Creek. Balls hit in that direction required someone to chase the ball over the hillside to the level area, or to our dread, our only baseball came to rest in a tangle of weeds and trees along the creek. Because baseballs were so difficult to obtain we ruled every ball that was hit to right field, which went over the hill, as an out—except for left-handed batters, who naturally hit in that direction. Those batters were limited to singles.

When a batted ball carried across the high chain-link fence separating the lower level from the jungle of brush bordering the creek, it necessitated a “time-out” and all of us climbed over the fence and into the weeds, hoping the ball had not traveled all of the way into the creek. Gene Barker was known as our “ball-hawk” because he had a knack for being the one who located the ball before any of us unintentionally located a snake.

Gene, and his older brother, Ronnie, were from a family of five children. Both of them were devout baseball fans, energetic baseball players and they had a classic big-versus-little-brother rivalry. They were very close, but nearly every game was delayed while they argued with each other. Gene was smaller than Ronnie, but had quick wrists which allowed him to closely compete with his older brother. Both were talented right-handed batters which made them players that sand-lot teams were built around.

We grew up in a time when there were no leagues below Little League. Many boys were disappointed at try-outs because the coaches actually cut all except the best players. Before each game, two of us would claim the right to choose teams. Seldom was favoritism a factor in choosing a team because each “manager” wanted to field a winning team. Although someone had to be chosen last, there was little or no embarrassment because everyone who wanted to play was a fairly decent ball player. In fact, most of them played on Little League, P. O. N. Y., and Colt League teams. To choose teams one of the boys tossed a wooden bat (metal bats were unknown to us), handle up, into the air toward the other boy who would attempt to catch the bat, with one hand, in a strategic location. After the catch, the boys would alternate grasping the bat, hand over hand, until the top hand, under the knob, determined who got first pick. Sometimes there was a pre-toss “discussion” of whether to allow “scissors” or “tops” during the hand over hand procedure. Someone usually called out “No tops!” because tops allowed a hand to grasp the knob of the bat as a final move allowing that boy to turn defeat into victory. Scissors meant that if there was a small space between the top hand and the knob, a first choice could be salvaged by the other boy opening his index and middle fingers and fitting them, scissors like, below the knob. The scissors option, which was not limited to the last move, generated some mathematical calculations (although we did not know it at the time) as the turns alternated toward the top of the bat. First choice (equivalent to a first draft pick) was always Ronnie followed by Gene and on down the line according to ability.

We established an imaginary left field foul line that extended from third base to the first outside corner of a stairwell near the far end of the apartment building. Batted balls hitting the brick wall made for some crazy caroms and exciting plays at second base. Even though batted balls reaching the street were home runs, we ruled that a foul ball that was caught was an out even though the ball was out of the playing field. The year before we outgrew our ball field, Ronnie was able to hit the ball over the top of the building! Just determining whether it was fair or foul caused some heated arguments, but the most vehement arguments erupted when Gene would stand in the street beyond the huge building unable to be seen by Ronnie. A teammate would stand on the top of the hill, in sight of home plate, and tell Gene when Ronnie hit the ball. Gene, an excellent fielder, would catch the fly ball, sometimes narrowly missing passing cars, before the ball hit the pavement. The brothers never came to blows and Ronnie would finally accept his fate and walk away angrily muttering.

One particular home run was a “one in a billion” occurrence. I do not remember who hit the ball to straight away center field, but it coincided with a passing dump truck full of sand. The ball landed in the sand without alarming the driver who continued on down the road ignoring our shouted pleas to stop. That ended our game for that day.

In left center field, at the base of the hill that served as our home run fence, there was a wide circular clump of shrubbery. Any ball going into those bushes was in play and the fielder had to go in and retrieve it. Many an outfielder, who chased balls into the tangle of bushes, went home looking like he had been attacked by an angry cat. Between the bushes and foul territory there were metal cloths line poles which presented outfielders with serious obstacles, especially if cloths were hung on the cloths lines.

Once, someone hit a ball through an apartment window. It hit the kitchen table and, amazingly, ricocheted back out through another pane of glass. At first, broken windows caused us to make a hasty retreat. As we grew older, and more brazen, we would remain and start yelling for an imaginary kid to “come back” whenever an apartment occupant, looking for the culprit, poked her head out of a just broken window.

Broken window complaints caused the Housing Authority to assign the maintenance men to attempt to keep us from playing baseball on the lot. Often we had to abandon our game and run when we saw the men coming between apartment buildings toward the ball field. At one point they removed the handle from a faucet which was located between apartment buildings inside a garbage pit. That eliminated a source of between inning drinks of water for the ball players. Finally, the maintenance men erected a sign proclaiming “Absolutely No Ball Playing Allowed in This Area”. The sign was placed just behind where our pitcher stood so the sign only became an obstacle making it more interesting for infielders trying to catch pop-ups.

Sometimes, to avoid the Maintenance Men, we would carry our equipment and walk (some would bicycle hauling a friend on the cross bar or handlebars) to the city maintained Legion Field recreation area. To get there we passed by a junk yard and trash land-fill. When we arrived we frequently could not play because city crews would be working on the field or teams would be practicing. Other times we would go to the more distant Cabell Field where we gathered with other West Side boys. In our late teens, Ronnie and Gene could hit a baseball off the railroad trestle that passed high above and beyond the left field fence. On a couple of occasions we rode bicycles to Watt Powell Park (a distance of about twenty miles round trip), climbed over the fence, played a few innings and then climbed the fence again to head home.

Baseballs were a prized possession to us. When we were younger we sometimes had to peel the black electrical tape from the broken bats we used and wrap it around the strings inside the cover of a baseball to keep a game going. Keeping a supply of baseballs required a bicycle journey to Watt Powell Park in the evening. Once there we had to compete with several other boys trying to get the batting practice home runs from the AAA baseball teams. The competition was fierce and fights sometimes broke out as boys chased down the baseballs. Gene had the edge because he could catch the balls due to his experience of successfully shagging fly balls despite the many Manor ball park obstacles. Once, Gene settled under a batting practice home run which glanced off an overhead wire before hitting him in the forehead knocking him unconscious. Ronnie retrieved the ball before checking on Gene.

During the games there was constant chatter of phrases like “hum baby, “swing the bat”, “you should have had it”, and “nice catch”. We did not have benches, so I was the nearest thing to a bench jockey with incessant teasing and encouraging my friends. There were many arguments over fair/foul and out/safe decisions. These were usually settled by, “You got the last one, so we get this one”. Fighting was common in the neighborhood, but I do not recall any serious fights during the baseball games. This was good for me since I was the only player wearing glasses, and broken glasses would have ended that game for me. Along with the scratches (from bushes and brush) there were bruises (from collisions with other boys and cloths line poles), busted noses or mouths (from getting in front of batted balls bounding erratically on the clumpy grass), skinned knees and strawberries (from sliding into bases)--but no serious injuries during the ball games.

Many personalities participated in those baseball games from 1956 to 1966. Each boy was proud of his batting stance and, like the way they uniquely held their bats, each boy was different from the others. Some were stocky; others lanky; some were frail and a couple were robust. There was the “loveable fat kid”. He often was yelled at for his slow speed and seemingly lack of competitive drive. Still, he was a fairly tough kid like all of the ball players. One of the small skinny boys took a throw at home plate which hit him in the chest. Rather than cry, he dropped his glove, left and did not return to the game. There was Jo-Jo and June Bug (two of five brothers), Little Jim, Jamsie, Twinkle Toes, Hot Rod, The Phantom, Corky, Pee Wee, Spike, Butch, Tank, Tadpole, and Water Arm. Water Arm, a freckle faced red-head, was a pitcher who irritated the Barker brothers with his unorthodox pitching motion. Many times, Gene, or Ronnie, flung their bat away in exasperation after lofting an easy fly ball because of Water Arm’s pitching.

With them were Eddie (who became a steel-worker), Richard (policeman then banker), Gary (veterinarian), Steve (television station employee), David (telephone company worker), Joe (coal miner), Mark (chemical operator), and Odie (salesman). There was Danny, Keith, Bobby, Mike, Ken, Donald, Abie, Paul, George, Bobby, Terry, Billy, Randy, Tim, Frankie, Jack, and Johnny, Allen and Alan--and many others who are only faded memories to me. Gene recently retired after a long career with Kroger. He played in a men’s baseball league while in his early fifties. He and his wife, Sheila, bought a house a few hundred feet from Watt Powell. As an adult Gene could leisurely stroll along and pick up the batting practice home runs because boys were no longer interested in them.

There were Manor boys who ended up in prison and one of our contemporaries was killed in a bar-room fight. Interestingly, those particular boys spent very little time playing baseball. Sadly, not all of the baseball playing boys lived long and reasonably successful lives. Danny died of a heart attack in his forties. Steve committed suicide in his thirties. Little Jim, became mentally ill and starved to death still living in a Manor apartment in his fifties, and Rickey lost a leg in a motorcycle accident. One of the Gary’s died of alcoholism in his forties. Ronnie Barker was married and a father when, at 37 years old, he died from a blood-clot as a result of an injury he received during a soft-ball game in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Eventually we played our last baseball game behind the brick building. We grew up and moved out of the Manor to make our way as adults. Several of us served around the world in the military. We never forgot the hot summer days of choosing teams in the shadow of the brick building. Inside that apartment building there was the misery of substance abuse and broken homes. In the front of the building there was the violence that earned the Manor its reputation. But, behind the brick building there was another world—a world of Yankees and Dodgers playing in front of throngs of cheering fans. We played on a true field of dreams. The experience of negotiating for the good of the group and operating as a democracy was established during those hours of playing pick-up baseball games. On the Manor ball field we learned to accept responsibility for our short-comings because dropping a pop-up, booting a ground ball, or making the dreaded blunder of knocking the precious baseball over the hill were actions that could not be hidden. On our old ball field memories were made and character was developed that carried the ball playing boys out of the Manor into man-hood, around the bases, and over the hill of life toward home.

NOTES:

A sports columnist included the following in a 1962 column. The “upper end” of Copenhaver Drive has done more than its share in producing boys’ baseball stars. Thee are no less than seven living in this section and five of them made All-Star teams this summer. Jo Jo Arthur and Karl Priest (McClure’s) made the Pony League All-Stars; while Jimmy Blain (Young’s), Mark Hall (Purity Maid), and Steve Mallory (Engineers) were named to the Little League All-Stars. They have playing companions in Ray McKeand (Optimists) and Eddie McKown (Merchants), who played their first year and were a little short of being named on the All-Stars. (Actually, there were more boys that lived in this part of the Manor, but these were the ones who were on teams that year.)

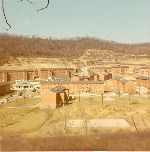

The following pictures were part of the article. All were in B &W. The one of me in my (2006) stance

(standing where the old “home plate” laid) was in the form of a baseball card and the caption compared a baseball batting stance to a fingerprint. It over-lapped my 1966 high school photo. Only the western half of the Manor was published. The eastern half is where we lived and the "ball field" can barely be seen in the middle right edge of the photo. Other photos are of me pointing to where we used to play which is now a fire department; Gene Barker

and me (We are standing where he used to snag fly balls that came over the building. My building is behind us. The new house stands where another Manor building once set.);

Corky Jones and me behind my apartment; “Little” Jimmy and me sitting on a railing (The small boy was unidentified in the article, but he is Eddie Gillispie who was too young to play ball with us).

(Click on each picture for a larger image.)

|

Manor 'West"

|

Manor "East"

|

|

|

|

|

|

The photo below is a 2008 reunion of some Manor "boys" taken at a West Virginia Power baseball game.

The guys are (left to right): Eddie McCown, Ray McKean (Twinkle Toes), (Hot) Rod Friend, me, Gene Barker, and Rick (Water Arm) Thornton.

Other baseball photos are HERE.

More about Orchard Manor

LEGACY INDEX

|